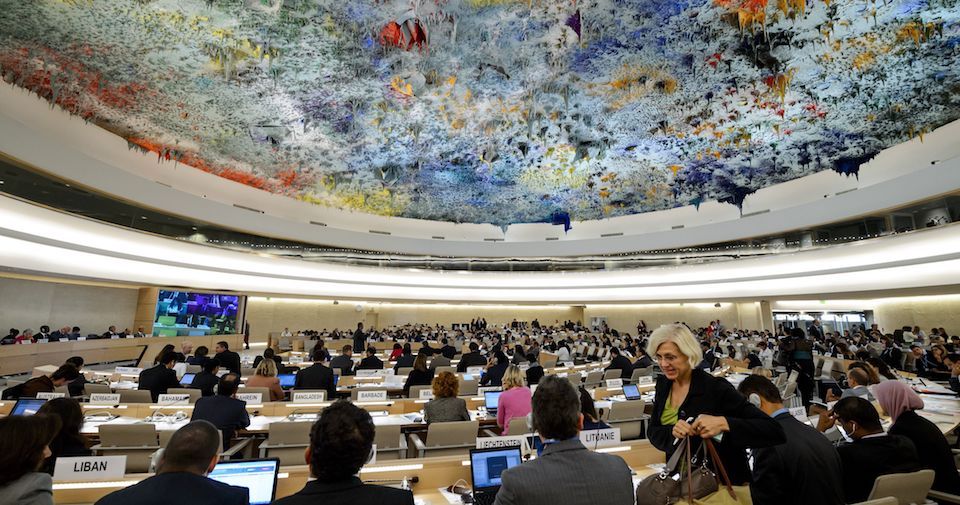

38th session of the Human Rights Council - Opening statement by UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Zeid Ra'ad Al Hussein

Opening statement and global update of human rights concerns by UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Zeid Ra'ad Al Hussein at 38th session of the Human Rights Council

18 June 2018

Mr. President,

Excellencies,

Distinguished Delegates,

Colleagues and Friends,

As this is my last global update to the Human Rights Council in a regular session – and before I turn, once again, to the important matter of access and cooperation – I wish to draw on some final reflections.

I heard recently a UN official telling others there is really no such thing as universal human rights, musing that they were picked from a Western imagination. I remember thinking to myself that the Universal Declaration of Human Rights – the most translated document in the world – was negotiated by the same political leaders who poured universal values into the Charter, creating the United Nations. Is the UN also then somehow not universal? Were its values sourced only from a Western tradition – unrepresentative of the rest of the world?

No. A clear rejection of this comes from a look at the negotiating record itself. The San Francisco Conference, which established the UN, was a circus of sound shaped from many tongues; its result was not a solo tune from a Western instrument. Had that been the case – had the countries that joined the organization believed they were being pinned to alien, Western values – why then did they not stream toward the exits? Why did they not withdraw from the UN?

But then why is the Universal Declaration, and the whole body of human rights law that followed it, the object of so much attack now –- not only from the violent extremists, like the Takfiris, but also from authoritarian leaders, populists, demagogues, cultural relativists, some Western academics, and even some UN officials?

I have spent most of my career at, and in, the UN. What I have learned is this: the UN is symptomatic of the wider global picture. It is only as great or as pathetic as the prevailing state of the international scene at the time. I also have come to understand how weak human memory is. That to many people history matters only in so far as it can be unsheathed and flung into political battle: they do not view it as a service to deeper human understanding.

There is a dangerous remove and superficiality to so many of our discussions, so much so that the deepest, core issue seems to have been lost on many.

Is it not the case, for example, that historically, the most destructive force to imperil the world has been chauvinistic nationalism – when raised to feral extremes by self-serving, callous leaders, and amplified by mass ideologies which themselves repress freedom. The UN was conceived in order to prevent its rebirth. Chauvinistic nationalism is the polar opposite of the UN, its very antonym and enemy. So why are we so submissive to its return? Why are we in the UN so silent?

The UN’s raison d’être is the protection of peace, rights, justice and social progress. Its operating principle is therefore equally clear: only by pursuing the opposite to nationalism – only when States all work for each other, for everyone, for all people, for the human rights of all people – can peace be attainable.

Why are we not doing this?

Those of us in the UN Secretariat, originating from all the 193 Member States, work collaboratively and we do not answer to any State. In contrast, too many governments represented at the UN will often pull in the opposing direction: feigning a commitment to the common effort, yet fighting for nothing more than their thinly-thought interests, taking out as much as they can from the UN, politically, while not investing in making it a true success. The more pronounced their sense of self-importance – the more they glory in nationalism – the more unvarnished is the assault by these governments on the overall common good: on universal rights, on universal law and universal institutions, such as this one.

And as the attack on the multilateral system and its rules, including most especially international human rights law, intensifies, so too will the risk increase of further mischief on a grander scale. The UN’s collective voice must therefore be principled and strong; not weak and whining, obsessed with endless wrangling over process, the small things, as it is the case today.

If my Office, of which I am very proud, and I, have gotten one thing right over the last few years, it is our understanding that only fearlessness is adequate to our task at this point in time. Not ducking for cover, or using excuses or resorting to euphemisms, but a fearlessness approaching that shown by human rights defenders around the world – for only by speaking out can we begin to combat the growing menace of chauvinistic nationalism that stalks our future.

I appeal to you to do more, to speak louder and work harder for the common purpose and for universal human rights law, to better our chances for a global peace. [...]